Fits And Starts

Detroit’s Maurice Malone persist on the path to fashion design success

By Holly Hanson Detroit Free Press staff writer February 17, 1998

New York – Like most fashion designers, Maurice Malone clearly remembers the first garment he ever made.

But where most. Designers recall whipping up doll clothes at age 4 or sewing prom dresses for their high school chums Detroit native Malone was a relatively ancient 19 before he got around to stitching up his first creation, a suede Jughead hat like the ones he’d seen on MTV.

At the time, he had abandoned his first career choice, producing special effects for movies. Bored and stuck with only a pool table and a sewing machine for amusement, he started to work on the patterns for the Jughead hat he wanted.

Soon, his friends were lining up to buy not only the hats, but also other clothes Malone was designing in a makeshift studio in his mother’s basement. He started selling his designs to several boutiques in Detroit and its suburbs.

It was a promising start. And if this were the typical fashion-designer profile, it would only be a matter of time before a chance meeting with a major retailer with rocket the young designer towards fame and fortune in New York.

But that was not the case for Malone, 33, who could also list club owner, photographer, musician and bike messenger on his resume. It would be more than a decade before he finally found a place among New York’s fashion stars.

Thanks to his mother, though, he was blessed with talent and drive. “Maurice always likes to create. He would always like to be by himself, so I guess he was creating then,” said Osheeleen. Malone, and interior designer who lives in Detroit. “Anything he started, he’d always try to finish.”

Good thing, too. For the fashion business presented more than a few obstacles. For one, Maurice couldn’t sew.

“I ordered how-to-sew books from the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York, and I looked at clothes to see how they were made,” he said, sitting down for an interview in the New York office of his public relations firm. “I was always good at coming up with a solution of how to do things, and I could do it so fast. I felt like I could learn and overcome every obstacle.”

Then there was the need to raise money to finance his growing business. He got a job delivering pizza, but that lasted only until his clutch gave out. No problem, he figured. He gave him more time to sew.

With family and friends as investors, Malone went into the fashion business in earnest in 1984, calling his company Hardwear by Maurice Malone. He may leather coats, hiring friends to do the sewing because professional help was so expensive. “I ended up at night taking everything apart and putting it back together because it was done wrong, Malone said.

Maurice Malone persist on the path to design success

Hardwear was a hit, though, and the order streamed in. But like many young fashion businesses, Hardwear could not keep up with the orders and maintain the quality customers expected. After four years Malone was forced to close down.

He wasn't idle for long. At 24, he opened Underground Nation on Woodward Avenue in Detroit, a private dance club that serves coffee and soft drinks, but no alcohol. Malone hosted parties at night, sewed clothes by day.

His club, too, was a success – at least until Detroit police begin citing him for operating without a license. Although Malone eventually got a state license that classified the club as a private nonprofit corporation, he closed the club in the summer of 1990 and move to New York.

When he found no takers for his fashion designs, he took a job as a bike messenger, planning to design and sew at night.

His job ate up 12 hours a day, and by the time he got home at night he was so tired, he could do little but sleep. Even then, he barely had enough money to buy food. Yet after four months, he quit the day job.

“I decided I didn’t move to New York to be a bike messenger,” he said. “The first thing to do was stop delivering packages.”

He lived on hotdogs, rice, and spaghetti. He was so poor that the only fast food he could afford was an occasional slice of pizza – so long as he bought it in Brooklyn, where it cost $1, and not in Manhattan where was $1.50.

Eventually, he found a partner who agreed to finance a line of boxer shorts and hip-hop clothes called Label-X by Maurice Malone. The designer in his backer never agreed on much more, though. Malone wanted to get exposure for his clothes by giving them to rap stars and the cast of “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air”; the backer told him he couldn’t make money given clothes away.

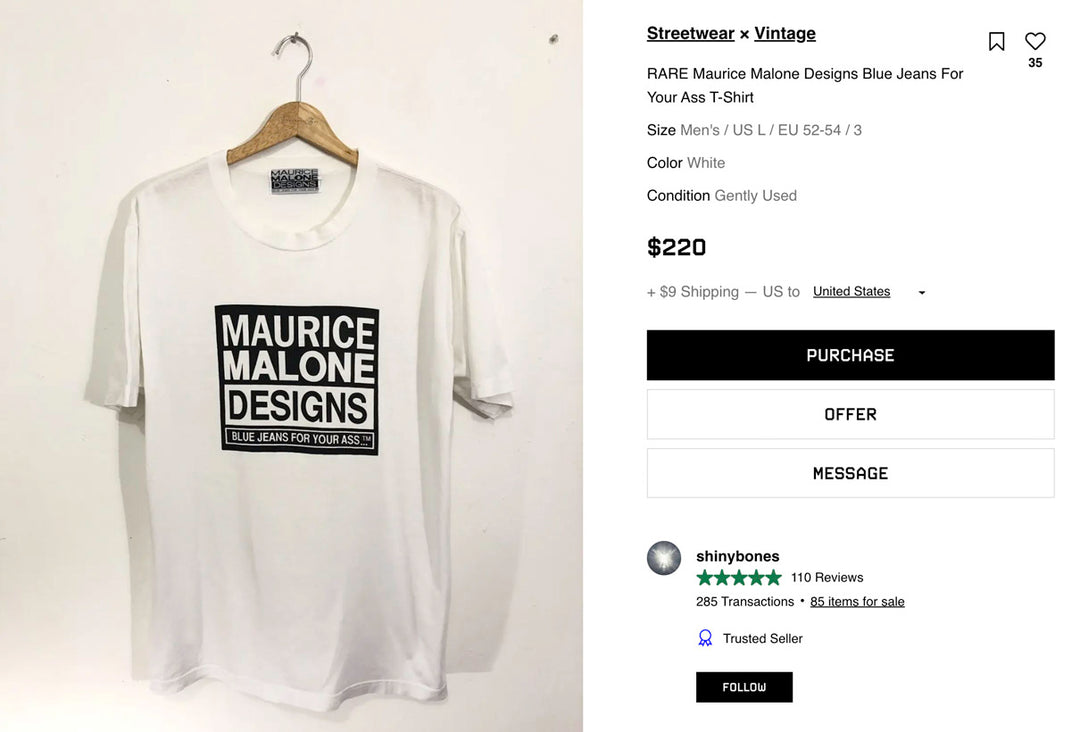

With the business failing, Malone moved back to Detroit in 1991. But he didn’t give up his fashion dream. Using rented sewing machines, he began producing jeans, fading them in a cement tub filled with rocks and bleach. He called this new line Maurice Malone Designs Blue Jeans For Your Ass. It too was a success.

Over the next few years, Malone had continuing troubles with business partners, including one situation that had to be settled in court. Under the term to the arbitration, he can’t discuss it. But his company finally began to click when he opened The Hip-Hop Shop in Detroit, selling his own designs as well as other labels. By the mid- ‘90s, he was operating a million-dollar business out of the bedroom of his mother’s house.

“We did $1.5 million in sales out of that room,” Malone said proudly. And by the time he moved back to New York in 1996, his annual sales had reached $2 million.

While Malone was happy with his company’s financial progress, he didn’t want to be known as a hip-hop designer. He had always done tailored clothes; now he wanted them to be the focus of his business.

To learn tailoring, he studied the construction of a $1,700 suit he’d bought to wear to his arbitration hearings. “I can make a better suit than this,” he thought.

He couldn’t do it alone, though, so he called on Tom Smith, the Bergdorf Goodman salesclerk who sold him the suit. Within a few weeks, Smith had agreed to help Malone develop a suit line.

“When I first met Maurice, I didn’t know who he was,” said Smith, who is now vice president of Maurice Malone’s company. “I had to do my own research on who he was. There were a lot of things that impressed me: the fact that he was so young and involved with the hip-hop movement, which I wasn’t really familiar with, and that he wanted to go into a completely different direction. I found it to be a challenge and that’s what interested me.”

To really make an impression, Malone decided to try for a slot to show his designs during New York’s for menswear week, held for retailers and the fashion press. He made a presentation and was placed on the schedule. Now on the pressure was really on. He had about six weeks to come up with a collection of suits.

But a tight deadline has never stopped him before. In February 1997, Malone proudly made his New York debut, showing suits as well as jeans and sportswear. “After that first show,” Malone said, I” started to be taken more seriously.”

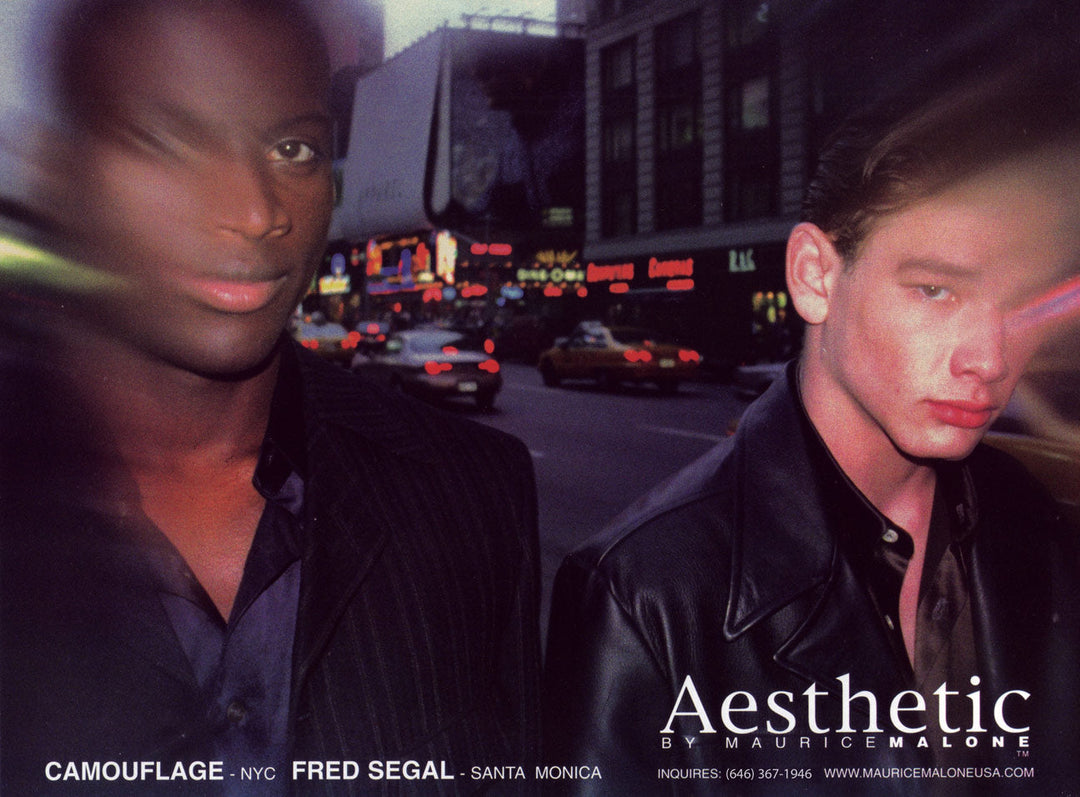

But not seriously enough. Though he’d been able to sell jeans and sportswear to small boutiques across the country, he was hoping to a major retailer for suit collection, made in New York of Italian fabrics, priced at $650 and up.

Malone wanted his tailored collection to hang in the Designer area, but most stores wanted to put his suits alongside his sportswear. No, thanks, Malone said.

I’ll wait until you think we’re big enough to be in the designer collections,” he told the stores. “I’m not going to affect the future of my company by giving in.”

As a result, his suits are available at only a handful of stores, including Fred Segal in Los Angeles. They are not available in metro Detroit. Last year, Malone decided he needed professional public relations help. He went to Showroom Seven International, which represents a number of designers in New York. Karen Erickson, a partner in the firm, is a Michigan native, and she felt an immediate connection with Malone.

“I looked at his press clippings, and I see this very handsome-looking guy who has a tremendous amount of charisma, and I immediately said, ‘Is he from Detroit?’ I could feel it,” she said. “And there’s like a Michigander camaraderie that does exist.” Still, Erickson was looking for more than camaraderie.

“Maurice understands what people want to wear,” she said. “He also understands what he wants, and he’s able to translate his desires and both a casual and a sporty way. I think he has tremendous potential.”

So, apparently, do the fashion professionals who nominated him for the 1997 Perry Ellis Award for New Fashion Talent in Menswear, an award given by the Council of Fashion Designers of America. Malone lost to newcomer Sandy Dalal, but he wasn’t particularly disappointed.

He had figured he would have to work in New York for two years before he will win the award, and here he was, being nominated a year ahead of schedule.

Don’t think for a minute, though, that Malone is now content to coast. “I want to take fashion to another level so that kids want to grow up to be fashion designers,’ he said.

“I look at Michael Jordan and I get inspired by his performance playing basketball,” Malone said. “He plays a level above everybody else, and the talent is coming up because of him. I want to help people get better and I plan to do that.”

Malone’s company did $5.5 million in business last year and he expects sales to reach $8.5 million this year. That’s encouraging. He’s also moving his showroom from Brooklyn to the heart of Manhattan’s garment district. That’s encouraging too.

And should he ever lack for motivation, he need only look out the window of his new 18th-floor showroom. There, directly across the street, is the massive headquarters of Tommy Hilfiger, perhaps the most ubiquitous label in menswear.

Leave a comment