Interview: Talent In The Raw

The Fashion Mannuscript magazine published a great article for the cover story of their April 2021 issue. There were a few minor errors that could not be updated since the magazine has been, so I made the edits. Here's a copy of the full story.

By Sophie Hollis, Editor Fashion Mannuscript Published April 1, 2021

Williamsburg Garment Co.’s good jeans are just part of its DNA

If there’s one garment that appeals to just about everybody, it’s jeans. For many people, jeans are more than a staple; the perfect pair is something personal and storied. But Maurice Malone, designer, and owner of Williamsburg Garment Co. and his namesake brand, Maurice Malone, takes the universal love of denim to a whole new level.

“When it comes to denim, you have a few pairs of jeans that you wear over and over,” he said. “I can wear one pair of jeans three days in a row and the look could be a little bit different because everything else — my top, shirt, jacket, whatever else I might be wearing — changes up.”

Malone treats jeans like expensive suits, emphasizing fit above all else. Once called “the Steve Jobs of denim” by Fast Company (a personal hero of Malone’s), he abides by the classic advice, “Keep it simple.”

Williamsburg Garment Co. (WGC) is distinguished for a few big reasons. First, Malone uses raw denim, meaning that it hasn’t been laundered at all (and shouldn’t be, if you want it to have that nice, natural fade).

“A lot of people are used to laundered jeans right now — like, most of the mass market buys laundered jeans,” Malone said. “But real denim enthusiasts like the raw denim, the way it was made back in the day when denim was first being made.”

Water consumption during production is one of the biggest criticisms against the denim industry, with The Fashion Law reporting that the cotton needed for a single pair of jeans requires 1,800 gallons of water on average — and that’s not including the laundering process. Raw denim cuts that second phase of water consumption down to zero and prevents some of the toxic chemicals in the dyes from leaching out into the environment. Plus, Malone argues, raw denim just looks better.

“Most washes look artificial,” he said. “You get a really good fade starting your jeans from raw and just wearing them without washing them and just letting them age naturally.”

And to score a few more environmental points, WGC offers jeans repairs and tailoring. In fact, adjusting and customizing existing jeans has become the company’s primary business since the onset of the pandemic.

“You’d be amazed at how many people send in jeans to get perfected or repaired because they don’t want to get rid of their favorite pair of jeans,” Malone said. “People, once they have a jean that fits, they want to extend the life as long as possible. They’ll spend more than it costs to get a new pair of jeans to keep that jean wearable that they love.”

When Malone first founded WGC, he manufactured in China, and his business was primarily in women’s jeans — 60% to 40% men’s, he estimated. But after two years, he moved production to the U.S., and the shift gave menswear a chance to surge ahead.

“Being named Williamsburg Garment Company, a lot of people assumed we were made in the U.S.A.,” he said. To test out a potential move, WGC made a tester called Hope Street (named after a street in Brooklyn, as all WGC jeans are now), and it was the most popular design despite its slightly higher price. Since 2014, everything has been made in the States.

Malone’s love for Brooklyn runs much deeper than his denim tribute to the borough. He’s been in Williamsburg for over 25 years, which he says reminds him in some ways of his hometown, Detroit, Michigan.

“I moved to Brooklyn the first time in 1989,” he said. “I wanted to get closer to New York City because it was the fashion capital of the world, and I wanted to learn more.”

As a teenager, Malone was making as much money as his friends with regular jobs by selling his own designs. His first hit was a hat inspired by Jughead’s crown beanie from “Archie.”

“When I started making hats, I kinda just taught myself how to sew, and I would go to the local library and read how-to-sew books,” he said. “I would drive up to F.I.T. every couple of months or a couple of times a year, buy their school books or magazines out of the bookshop that teaches you how to do stuff, and it just went from there.”

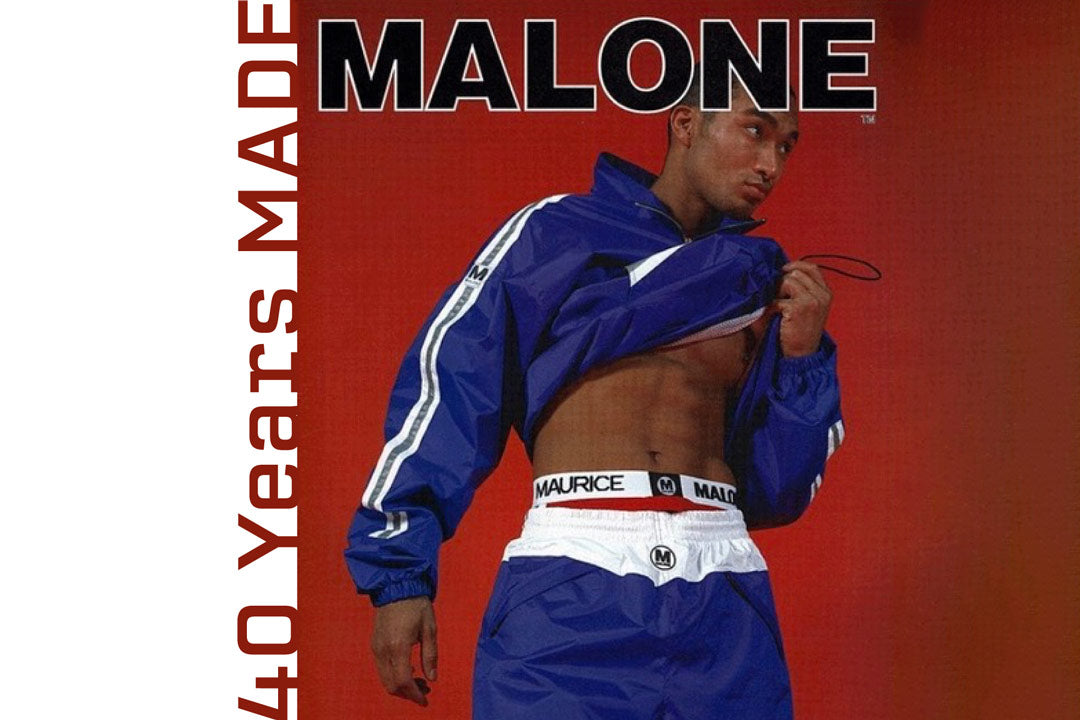

A falling out with a business partner forced Malone to move back to Detroit for a stint, where he introduced the city to New York hip-hop — and his signature style.

“It was so different from the parties and the music scene in Detroit, so I thought I could go back to Detroit and give people the flavor of New York hip-hop,” he said. “At the parties and events, I had a table with hats and T-shirts and whatever I made that week, and the hip-hop community started wearing my clothes.”

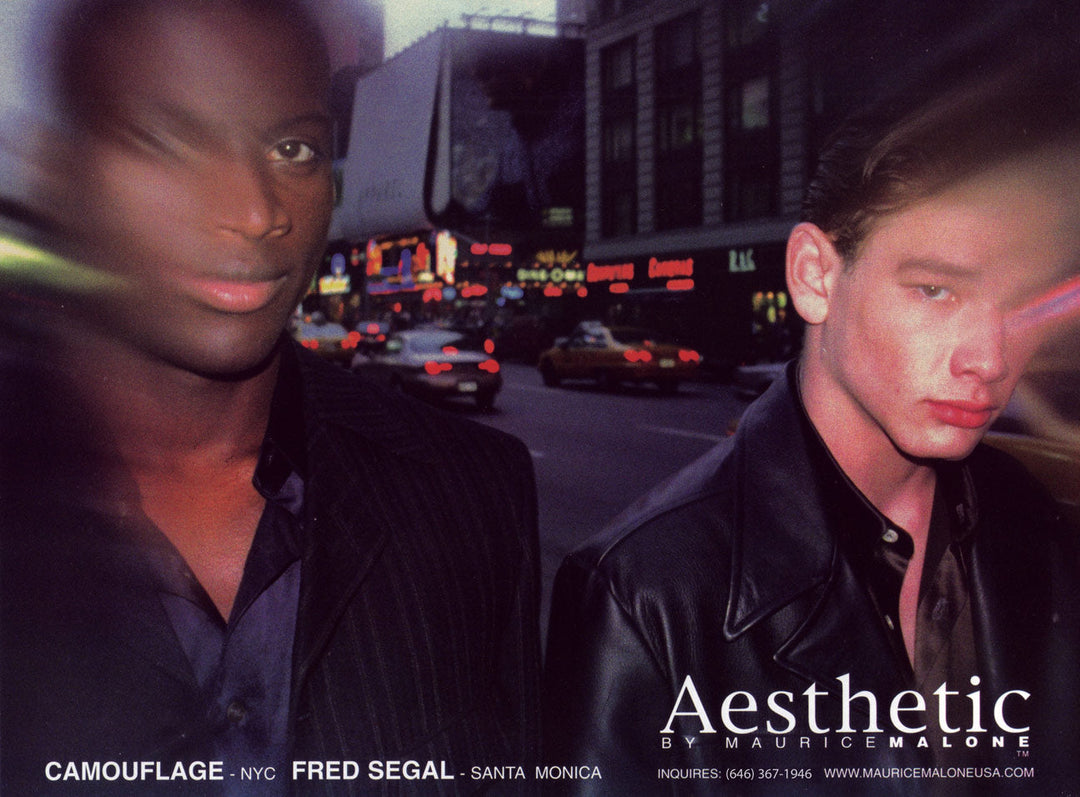

Brooklyn felt the return of Malone in 1995, and he’s been there ever since, building on the Maurice Malone brand and WGC. His self-taught expertise and experience have even helped him endure the pandemic economy.

“I saw the business going online a long time ago,” Malone said. “To the people that bought our jeans, I'd ask, ‘Are you online? How’s your online business?’”

Aside from a special partnership with Brooklyn Denim Co., Malone stopped selling WGC in stores about three or four years ago in favor of a digital model.

“Just dealing with retailers — it was more work than was worth it,” he said. “We don’t have to deal with a retailer wanting things back or a something sale or discounts or whatever.”

Without naming names, he mentioned that a bad experience with a department store was “the straw that broke the camel’s back” and steered him away from wholesale for good.

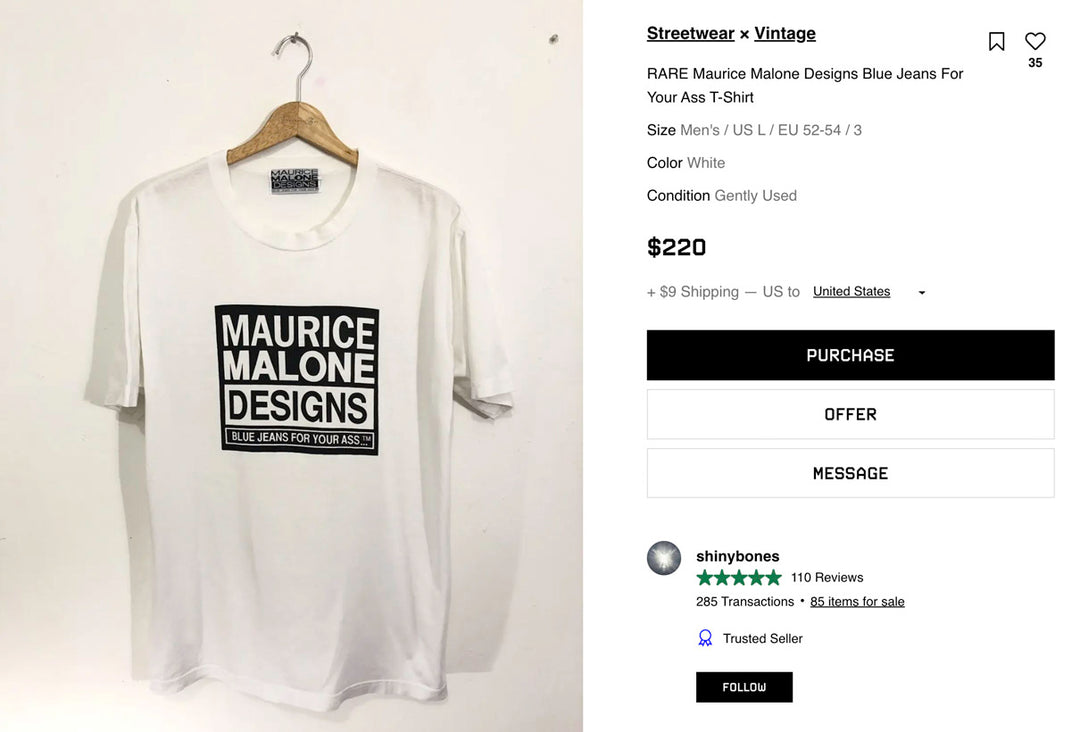

“They didn’t really care about our brand,” he said. “My thing is, the best way to protect your brand is to be in total control of it. Because other people, they can blow your brand up, but they can also destroy it when they’re done with it.”

Lest you mistake Malone’s denim enthusiasm for snobbery, it’s clear from his website and his genuine enthusiasm for talking all things jeans that the expert is eager to share his knowledge. He’s also hoping to mentor a few up-and-coming designers in the near future, and for the past two years, he has funded scholarships for Black designers to participate in the Parsons x Complex Streetwear Essentials certificate program.

“There’s so much bad information out there,” he said, explaining that he got tired of customers telling him things they heard that aren’t true. “We tried to become a reliable source of information for people who just love denim, and hopefully, they’ll try our brand or give us a shot when it comes to alterations and repairs.”

As shopping conditions improve with the distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine, Malone plans to re-focus his energies on the Maurice Malone brand and on expanding his WGC model to other cities for denim alterations and repairs — with a continued emphasis on online business.

“The future is about being able to give consumers exactly what they want, online,” he said. “More than ever, consumers drive business.”

Leave a comment